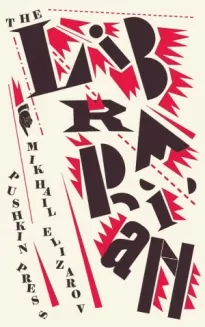

The Librarian

- Автор: Михаил Елизаров

- Жанр: Современная проза / Социальная фантастика

- Дата выхода: 2015

Читать книгу "The Librarian"

A LITTLE DEBT

THE TEMPORARY CALM came to an abrupt end on 27 June. During the afternoon the phone rang. I blithely answered it because I was sure it was my father calling, and I was even ready to serve up his next portion of: “The renovations are progressing, it’s a nice town, the people are friendly and food prices aren’t high here.”

“Comrade Vyazintsev?” a man’s voice asked, and I felt the fear flood through my belly like boiling acid.

“Yes,” I replied in a dead voice. That form of address—“Comrade Vyazintsev”—could only mean one thing: the call was for the librarian of the Shironin reading room.

“Alexei Vladimirovich, this is Latokhin here. We met at the meeting…”

The gammy-legged leader of the Kolontaysk reading room. I remembered him.

“Good afternoon, Comrade Latokhin,” I said.

“Alexei Vladimirovich, we are sure that you will not refuse us your fraternal support…”

“Comrade Latokhin…”

“Alexei Vladimirovich,” Latokhin said insistently, “I know you lost four members only recently, but without us the outcome of the satisfaction would have been even more lamentable! And, after all, you did sign a document…”

“Comrade Latokhin,” I said, suddenly realizing that I had offended against etiquette, “do not think that we are refusing. I only arrived here very recently, you know. It would be best for you to talk with Margarita Tikhonovna…”

“But, after all, you are the librarian!” Latokhin exclaimed in astonishment.

“Yes, but that is still a formality. Margarita Tikhonovna decides everything…”

“What childish nonsense!” Latokhin muttered, and hung up.

That evening a council of war was held on Shironin’s Guards Street. Everybody attended except Vyrin. Margarita Tikhonovna came in dark glasses—her left eye was completely covered by the swollen, mutilated eyelid. Sukharev’s hand dangled in a gauze sling like a white claw, with the fingertips poking out of the plaster like potato shoots. Lutsis had almost recovered from his concussion, although he felt sick in the car and he didn’t read the Book, complaining of dizziness and nausea. Anna Vozglyakova’s cracked collarbone had already knitted together, but it still ached.

Unfortunately my hopes of sitting it out as a nominal presence were not realized. After a brief report on the state of affairs, Margarita Tikhonovna dumped the burden of chairmanship on my shoulders.

What had happened was this: our Kolontaysk neighbours were being menaced by a migrant library that had lost all its Books as a result of armed skirmishes and was now trying to collect them back together, like scattered stones.

The nomads’ home territory had once been the town of Aktyubinsk. They used to have three Books of Joy, a Book of Memory, a Book of Endurance and a Book of Fury. The readers called themselves Pavliks, after their first librarian, Pavlik. The Aktyubinskites had been rendered destitute not by Mokhova, but by Lagudov a year before Neverbino, and then marauders had hit them really hard, reducing the substantial group to the size of a small reading room. The Pavliks had left their habitual place of residence to save their lives.

There were twelve of the exiles left, and they had a Book of Fury, capable of plunging anyone into a blind frenzy. This Book didn’t bring any pleasure, but the aggressive emotion that it imparted was very useful when it came pouring out on the battlefield. It is not clear what the subsequent destiny of the reading room would have been if Semyon Chakhov, a stage designer, had not come across them. He had a stolen list of redistributed books, which showed who had received the books stolen from the Pavlik library. It was the appearance of the list that provided the stimulus for the reading room’s revival. The Pavliks decided to restore justice and take the Books back. The first victim was the Orenburg reading room, which was unfortunate enough to own one of the Books of Joy that had once belonged to the Pavliks. The Pavliks slaughtered the reading room and won back the Book. From there their bloody route ran through Chelyabinsk and Kurgan. The Books of Joy were recovered. Ominous news came from Novosibirsk. The Aktyubinskites had taken back their Book of Endurance.

Naturally, the council kept an eye on the Pavliks, issuing warnings and threatening punitive measures, but with no result. The forces of the council always arrived at the battlefield too late, hypocritically complaining that the enemy was too elusive. It was clear to all right-thinking readers that the only reason for this elusiveness was that a ruinous raid by the Pavliks simply played into the council’s hands—the provincial reading rooms were disappearing.

The next target was the Kolontaysk reading room, which owned a Book of Memory. According to information received from the council, the Pavliks could be expected in Kolontaysk any week now. The council had promised Latokhin reinforcements, but the reading room’s greatest hope was their neighbours. Latokhin was right to be alarmed. The Pavliks had once again become a fully fledged library with a total of up to eighty readers. And apart from everything else, they had a Book of Fury and a Book of Endurance—irreplaceable battle Books; only the extremely rare Book of Strength could be better…

That was what I learned from Margarita Tikhonovna. And then she said:

“I propose that we should hear from our librarian, Alexei Vladimirovich.”

Unfortunately, the cowardly question that came to my mind was whether there was any elegant pretext under which we could renege on our debt to the Kolontaysk readers. I was too embarrassed to put the question directly and approached the subject obliquely.

“I’m new here… It’s hard for me to judge. Of course, the easiest thing is to regard this as entirely the Kolontaysk reading room’s problem and, after all, the Book of Memory did belong to the Aktyubinsk library…”

I paused, but no one volunteered to complete my train of thought and say, “If that’s the case, we have no business sticking our noses into all this.” On the contrary, they all waited for what would come next.

“We have suffered substantial losses; our own situation is far from easy…”

And again the response was attentive silence.

“Let us honestly consider whether we can refuse the Kolontaysk reading room…”

The Shironinites smiled. My words had been taken for rhetorical irony born of courage—with the bravado of: “Is there powder in the powder horns still?”

“Well, of course we can’t refuse,” Lutsis said merrily.

“It’s as clear as day,” said Sukharev, backing him up. “And anyway, we signed a piece of paper.”

“Lads, joking aside,” Dezhnev put in, “we have to decide how many people we send.”

Margarita Tikhonovna nodded.

“A good question, Marat Andreyevich. The Kolontaysk reading room sacrificed three warriors for us. I think we cannot send fewer than four people.”

“That’s fine,” Timofei Stepanovich declared cheerfully. “I’m always ready.”

Kruchina, Ievlev and Lutsis raised their hands like star pupils and Young Pioneers.

“Denis!” Marat Andreyevich exclaimed. “Where do you think you’re going? What kind of fighter would you make now?… Timofei Stepanovich and Fyodor Alexandrovich will go.” Marat Andreyevich looked at Ogloblin, who nodded eagerly. “Well, and, of course, your humble servant…”

“That’s three people,” Margarita Tikhonovna said quietly. “Who else, Comrade Dezhnev?”

“Let’s say Tanya. Or Svetlana. Or Veronika…”

“Svetlana can stay here,” Lutsis said stubbornly. “Why her? I’m more use in any case.”

“Denis, just think about it,” Ievlev boomed amiably. “Three of the Kolontayskites really did die for us, but that doesn’t mean we have to pay them back in corpses. What we want is a victory… You need to rest and restore your strength. But I don’t agree with Dezhnev either. Why take women?”

“Wait a moment,” Marat Andreyevich sighed. “Let’s think logically. Comrades Ievlev and Kruchina are the backbone of our reading room’s strength. We can’t really count on Sasha and Denis—don’t take offence, lads, but it’s true. Grisha’s position is obvious. Margarita Tikhonovna and Anna are not entirely well. Someone has to protect the Book and Alexei. And our beauties are splendid fighters.”

“I’m against Svetlana being chosen,” Lutsis declared categorically. “Why can’t I go, if I’m well?”

“Denis, you’re a grown man. Be objective about yourself,” Margarita Tikhonovna said sternly.

“Yes, yes, that’s right,” said Svetlana. “I’d be happy to join the men.”

“And I’d be even happier,” Veronika laughed.

“Comrades,” said Tanya, getting up. “Permit me to share my thoughts with you. Much as I hate to remind you… The Vozglyakov family…”—Tanya’s voice trembled—“… lost their dearest member only a month ago…”

When she said that, Svetlana’s lips started trembling, Anna wiped away a tear and Veronika, the youngest, lowered her face into her hands.

“Tanya,” Sukharev exclaimed reproachfully. “Why say that? It will take Veronika half a day to calm down now…”

“I’m sorry, but it was something that simply had to be said,” Tanya continued resolutely. “Obviously, the death of any reader is an irreparable loss. But a family is something else, after all. Our girls are strong people, but it wouldn’t be right to put them through the unnecessary trauma of more emotional stress. Perhaps they’ve given enough, eh?”

“Tanya, why are you making us look like some kind of egotists?” Anna said in a pained voice. “We’re equal here! We’re all equally precious!”

“What Tanya says is right,” Marat Andreyevich said with nod. “What has egotism got to do with it? You need to recover, to restore you spirits. Am I right, Tanya?”

“Bull’s-eye, Comrade Dezhnev. That’s why I propose that I go and I urge everyone to back me up! Well, after all, Alexei can’t go! Timofei Stepanovich, why don’t you say anything? It will be easier for you with me!”

“Thank you Tanyusha,” Margarita Tikhonovna sighed. “You’ve made everything very clear—clearer than I did. Right then, comrades, let’s vote…”

“And make it a unanimous ‘yes’,” Tanya threatened them jokingly. “Abstainers are my enemies for life!”

I felt a strange new feeling. Something like a pang of conscience. The voting came to an end, the others all went home, and the uncomfortable feeling swelled up inside me, so that by the evening my soul’s former timid shell felt as tight as a shoe one size too small…

In an attempt to smother this condition, I picked up the Book. This time everything was much simpler; the text didn’t slither about, and in two hours I had read the Book of Memory for the first time…