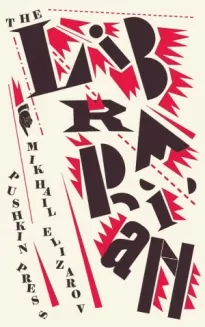

The Librarian

- Автор: Михаил Елизаров

- Жанр: Современная проза / Социальная фантастика

- Дата выхода: 2015

Читать книгу "The Librarian"

QUARANTINE

THE ANNIHILATION of the Uglies’ gang didn’t cause a big sensation in the town. The massacre near Urmut was mentioned twice in the faceless news on the local TV channel, somewhere between “the Khokhlakov family wish their dear mum a happy birthday, good health and every happiness” and a homespun advertisement for the Paradise furniture store. They said: “gangland killings”, “the staff of the café were not harmed” and “the investigation is continuing”.

We learned that we hadn’t got away scot-free with the operation from the librarian Burkin. The council was holding a session in Izhevsk, and Burkin had gone there to arrange some business of his own. It came as a complete surprise to him to hear a report by a member of Shulga’s clan about the events at Urmut. It was discussed prosaically, without any pathos, with the flat assertion that the Shironin reading room had carried out an unsanctioned “clean-up” without warning anybody about it. Someone in the presidium remembered that Burkin had given us help in the satisfaction, and he was forced to sign a pledge of non-disclosure. Vasily Andreyevich was very alarmed by all this. He sensed danger and, in defiance of the law, warned us.

It was too late to guess how our misfortunes had been discovered. Lutsis suggested that there could have been a spy among the down-and-outs whom the Uglies fleeced, and he could have reported to Shulga. We had to forestall any possible penalties and report the incident with the Uglies to the regional prefect, Tereshnikov, presenting events in the most favourable light. We prudently didn’t inform the council that Ogloblin had been killed. The last thing we wanted was inspectors and checks.

At first glance this move—the repentant guilty head that the sword does not hew—worked perfectly. We could not be accused of criminal concealment of the facts. The members of the council shrugged the matter off and muttered that we were obliged to inform them before the “clean-up” at the reservoir, not afterwards. It went no further than that. But unfortunately we had relaxed prematurely.

Yambykh showed up for what seemed like a trifling inspection. And on the next day, positively bursting with his own sense of importance, he declared that the reading room was under house arrest. The problem, which at first hadn’t even existed for the council, had suddenly in the space of a single day been inflated to the menacing proportions of a tribunal. And the most tragic thing about it was that the reader Ogloblin, who had disappeared like a little grain of sand in the sea of the world’s life, threatened to become a millstone round the necks of all the Shironinites. It was too late now to report what had happened to him; all we could do was hope that our inspectors wouldn’t notice he was missing.

Yambykh’s people scoured the town for a few days, trying to dig up dirt on us, but apparently they didn’t find anything. We didn’t want to provoke Shulga’s liaison officer unnecessarily and tried to comply with his absurd order not to leave our homes. During this period Yambykh contacted us twice.

Finally we heard from him a third time. “Comrade Vyazintsev!” his voice shouted down phone in shrill, triumphant fervour. “I have important information for you. Get the whole reading room together this evening!” I couldn’t tell what the cunning liaison officer was working up to. Probably Yambykh had sniffed something out and now he was trying to call our bluff with this general meeting. Then we would have to explain where our reader Ogloblin had got to. “Roman Ivanovich,” I suggested cautiously, “perhaps we don’t need to disturb everyone? Why don’t I just call Selivanova and Dezhnev? They’re our most senior and respected readers…”

Yambykh didn’t argue and set the meeting for seven that evening.

“When you get right down to it,” I reassured myself for the rest of the day, “why would he want to count us? He can only know about the Shironin reading room from hearsay. Even if he has been shown a group photograph of the reading room, he’s hardly likely to have remembered every Shironinite’s face.” That was what I thought. “Yambykh is only here to find out why the Caucasian bandits latched onto us.”

It was that evening when the prickly hospital word “quarantine” was first heard.

“To ensure the objectivity of our review,” Yambykh explained sparsely. “By the way, do you have mobile phones in the reading room?”

“Where would we get them, if I may ask?” Margarita Tikhonovna said with lofty indignation.

“Oh, come on… This is the year 2000,” said Yambykh, pulling a wry face. “A mobile stopped being a luxury item ages ago…”

“…and became an adjunct of moderate prosperity,” Margarita Tikhonovna concluded. “Something that we cannot boast of, I’m afraid. But what’s the problem, Comrade Yambykh? Do you need a cell phone urgently?”

“Not at all,” said Yambykh, waving the question aside. “The first requirement of quarantine is a total information blackout.”

“Meaning what?” Marat Andreyevich asked cautiously.

“We insist that all your reading room’s external contacts be cut off for the duration of the review!”

“Do we have to have our phones at home disconnected?” Margarita Tikhonovna asked.

“Unfortunately that’s no solution. The entire reading room is ordered to leave the town.”

“And where are we to go?”

“A place where you will be isolated. That’s what we have to agree on.”

“Listen, Roman Ivanovich,” I put in. “This is overkill. We have no intention of hindering your work. Why isolate us? We’re not jaundice cases…” I smiled, but Yambykh remained sullen and intent.

“Shironinites, stop pretending the purpose of the quarantine isn’t clear to you! Do you think we have no idea who warned you about the inspection? Eh, Comrade Selivanova?”

“I simply can’t imagine what you mean!” Margarita Tikhonovna said with an imperturbable shrug.

“Drop all the play-acting,” Yambykh said wearily. “You understand perfectly well.”

A chilly breath of leaf-fall August wind set the curtains fluttering. Yambykh slapped the greasy locks flung up by the draught back down against the nape of his neck. Even the wide-open window was no help against the suffocating smell of sweat seeping out of the short sleeves of his shirt.

“But can’t you manage without quarantine?” I asked, trying to coax the liaison officer, but I ran up against the reverse reaction.

“What’s bothering you? The fact that you won’t be able to swap your secrets?” Yambykh asked with a pointed glance at me. “In that case the question that arises is what about and who with. What will you tell me to report to the council?”

“What secrets, Roman Ivanovich? You imagine plots and conspiracies everywhere. It’s damned inconvenient. Our comrades have to go to work.”

“Take unpaid leave. You’re not children, you’ll have to cope. And anyway it’s only for two weeks.”

“Listen,” said Margarita Tikhonovna, refusing to give in. “I’m an old woman, and I’m not in good health. What if I become unwell?”

“It seems that Comrade Selivanova has failed to understand the seriousness of the moment,” Yambykh declared in surprise. “The fate of your reading room depends on the result of my investigation! Is that clear at least?”

“Without medical help I can die!”

“You should have thought about that sooner, and not gone organizing massacres before complaining about your health.”

“They’ve given a toady authority,” Margarita Tikhonovna exclaimed in a voice trembling with fury. “And he rolls around in it like a dog in shit!”

“We’ll pretend I haven’t taken offence,” said Yambykh, staring indifferently out of the window.

“Roman Ivanovich,” I said, grasping at a new idea. “Let us just move out to the country. Some of our readers have a private house outside the town. It’s a remote spot with no phone, perfectly suited for quarantine…”

Still looking off to the side, Yambykh tapped out a confused march on the table with his fingers.

“All right,” he said after pondering affectedly for a while. “I’ll accommodate your request. You can make the move tomorrow. The requirements are the same: all outside contacts and travel are prohibited. I urge you wholeheartedly to act responsibly, or the consequences could be disastrous.” He picked up a matchbox from the table, hooked out a match with his nail and clenched it in his teeth, like a cigarette.

“A day’s not long enough,” I said immediately. “Give us at least until the end of the week.”

“What’s the problem?” Twisting his grinning mouth, Yambykh poked between his samovar-like crowns with the match.

Margarita Tikhonovna turned away squeamishly.

“It’s a bothersome business, Comrade Yambykh,” I said, haggling. “Arranging leave, packing things, buying in enough food, organizing transport…”

“You used to have a minibus, if my memory serves me right…”

While I was feverishly trying to think what line to spin him, such as: we sold the RAF to pay our debts and cover our reader Vyrin’s medical costs… Yambykh fortunately forestalled my cumbersome lies.

“OK, I’ll give you two days. But no more.”

He wrote down the Vozglyakovs’ address and said goodbye, promising to visit us.