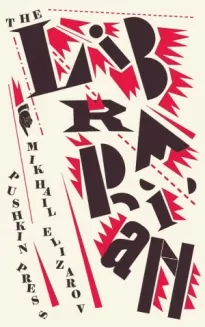

The Librarian

- Автор: Михаил Елизаров

- Жанр: Современная проза / Социальная фантастика

- Дата выхода: 2015

Читать книгу "The Librarian"

THE PAVLIKS

THERE REALLY WERE a lot of Pavliks, as many as a hundred white, blood-spattered mummies. It was a grisly sight. While they were still on the slopes they formed up into a bulging crescent moon, with a curve like a sabre, but they didn’t seem to be in any hurry to attack.

I focused on my own feelings and noted with satisfaction that there was no fear. The thoughtful Shironinites had hidden me away deep in the formation. On Akimushkin’s plan it was square number thirty-one. On the right I was covered by Tanya, with Timofei Stepanovich, Marat Andreyevich and Fyodor Ogloblin beyond her—I had no reason to doubt those people’s fighting credentials. On my left were the Vologda readers, and to reach me the enemy would have to smash his way through the barrier of their mighty axes—in the world outside the Vologdaites were a worker’s cooperative of lumberjacks. And the very sight of twenty-plus Kolontaysk “goalkeepers” was enough to reassure me that the enemy would never crush their ranks.

In imitation of the “Japanese style”, Kisling’s warriors had assembled armoured mantles out of thin steel pipes attached together like straw mats. Zarubin’s “Cossacks” looked tremendous dressed in light chainmail vests over red kaftans and carrying poleaxes and sabres. The turbans and kaftans of Tsofin’s warriors added a touch of menacing oriental colour to the ranks.

Akimushkin’s readers from Penza had come to the battle with their traditional gaffs, scythes and clubs welded out of water pipes or battle-axes decorated with pommels in the form of brass taps. Their padded work jackets, covered with blocks of plastic foam glued to their surfaces, looked like life-jackets. Akimushkin had said the greatest danger was not from stabbing and slashing, but from crushing blows.

It looked as if he was mistaken in his choice of armour. When the Pavliks came closer, I couldn’t see any hammers or axes. What I had taken from a distance to be spears looked exactly like rifles with attached bayonets.

I shook the imperturbable Vologda librarian Golenishchev hard by the shoulder.

“What about the general agreement not to use firearms?”

The answer ran through my head: “That’s right, the Pavliks don’t come under the council. All they want is to get their Books back. What do questions of ethics and honour mean to them! Now they’ll fire a few salvoes and Latokhin’s army will no longer exist.” That was the explanation for the Pavliks’ invincibility…

“Well, good for Chakhov, he knows what he’s doing,” Golenishchev replied. His voice was calm and slightly mocking. “Take a closer look, Alexei Vladimirovich. Those aren’t rifles. Only the bayonets are genuine.”

The Pavliks’ guns turned out to be something like crutches— perhaps originally they had been crutches, only now they had bayonets and massive butts faced with metal.

“I’ve been told,” Golenishchev continued, “that in Novosibirsk they dressed up as Kapellites. A psychological assault. Meaning they did a bayonet charge…”

“Well, naturally,” said one of the Kolontayskites. “A bullet’s a fool, but you can trust a bayonet.”

The Pavliks halted as if on command. There were no more than a hundred paces between them and us.

“Marat Andreyevich,” I whispered to Dezhnev. “What now? There aren’t any seconds, are there?… Who sets the rules in cases like this? Who monitors everything?”

“Why, no one does. It’s the two sides in the fight. Look, Latokhin’s already on his way with some lads… Now they’ll decide how to conduct the battle. The Pavliks already realize they don’t have much of an advantage, and they’re tired… Maybe our side will offer to buy them off or suggest some other compromise. Latokhin had good reason to gather all these people. To cool the Pavliks down a bit and make them think… I don’t want to make any guesses, but I’ve got a very good feeling about this, Alexei.” Marat Andreyevich smiled encouragingly.

The tense minutes passed one after another. We stood there, craning our necks, looking at the group of five Kolontayskites and the group of Pavliks who were discussing our fate.

I heard my name called and then Golenishchev’s. He parted the backs of the Kolontayskites and set off to answer the call, straight through the formation. I thought I’d misheard, but my name was passed through the ranks again: “Vyazintsev…”

“But what do they want Alexei for?” Tanya asked peevishly.

“We’ll find out in a moment,” said Ogloblin. “I don’t like this.”

I saw that Kisling, Akimushkin and Tsofin had left their brigades and set off towards the negotiations. Veretenov followed the librarians. When he drew level with them, he confirmed my summons.

“Latokhin is calling for Comrade Vyazintsev…”

“Where to?” Tanya asked cautiously. “Tell him Vyazintsev won’t go… Don’t go, Alexei!”

“Comrade Veretenov,” said Marat Andreyevich. “Let me go instead.”

“I don’t understand,” said Veretenov, confused. “Vyazintsev’s the one they want… He’s the librarian!”

“There’s nothing here to understand!” Tanya said harshly. “You go to that Latokhin of yours…”

The Kolontayskites looked at us in amazement.

“Hey, what are you two doing?” I asked quietly. “They’ve found a problem. I’m sure it’s just a standard formality…”

“And what if it isn’t?” Ogloblin asked dubiously. “Don’t go. Let Latokhin risk his own life, not yours. That’s not what we agreed…”

“I won’t let you go!” Tanya exclaimed, clinging tightly to my sleeve. “Marat Andreyevich! Come on, tell him!” she said with tears in her eyes.

I felt terribly embarrassed, especially since I’d already made my mark as a panic-monger.

“Marat Andreyevich, please, calm Comrade Miroshnikova down,” I said, adjusting my sleeve when it was released, and dashed after Veretenov.

The Pavliks were waiting for a decision. They looked identical, but I assumed that their leader, Semyon Chakhov, was the one in the centre of the group. This man was unarmed, but he was clutching a large bundle of sticky, bloody entrails, with dung flies sitting on the gleaming guts like motionless bronze sparks.

The other negotiators had slings round their necks, and their plastered forearms rested in them like infants in cradles. This was obviously a piece of Aktyubinsk swank, like sticking your hands in your pockets. The white motorcycle helmets on their heads were decorated with artfully applied bandages.

Chakhov had a good grasp of stagecraft. Even his entourage’s weapons were eye-catching and memorable. The maces were especially impressive—crude steel wires with clumps of concrete resembling meteorites, studded with broken glass, and forks with scummy deposits of dung on their prongs and deliberately broken handles. The hand of an artist was clear in everything. The weapons, like the Pavliks themselves, made your skin crawl.

Swaying as if he was exhausted, Chakhov wheezed in a low voice:

“We’ll wait on one side…” His hands twitched convulsively and he dropped the repulsive bundle. The stage-prop innards unwound and plopped onto the ground. The dung flies didn’t take flight—the insects were only scary junk jewellery.

Chakhov walked off and the ribbon of guts crept after him, with the rubbish that immediately stuck to it. I was aware that this was play-acting, but when Chakhov slowly pulled the guts towards him like an anchor chain, I felt a bayonet piercing my belly.

The Kolontayskites exchanged glances with Latokhin and left the librarians on their own.

And then Latokhin said morosely:

“Comrades, I need to consult with you. As I anticipated, the Pavliks don’t want a large-scale battle. I tried to resolve the matter by buying them off. Chakhov refused. Then I suggested an honest duel, one on one, with the condition that if he lost, the matter of the Book would be closed, and if I lost, then his library would get the Book. Chakhov says that since six reading rooms have intervened for us, it’s only logical that I face the music together with my allies, not on my own. In short, he insists on a collective duel, seven against seven… I implored him to limit it to fighters from our reading room—it’s only fitting for them to fight for the Book…” Latokhin sighed and shrugged, spreading his hands. “That didn’t suit Chakhov. He’s definitely a very shrewd and cunning individual, and he understands the lay of the land. I don’t know what I should do. I’m waiting for your advice.”

“The calculation is simple, elementary,” Kisling said with a frown. “If we refuse, there’ll be a bloodbath and many lives will be lost…”

“But we were prepared for that,” Tsofin said thoughtfully, “the compromise proposed by Chakhov is far from simple. And, to be quite honest, I’m not in great shape…”

My turn to say what I thought came.

“I won’t try to hide the fact that I have absolutely no experience. This is only the second time I’ve taken part in an event like this. Don’t think I’m being cowardly, but I might let you down…”

“Come now, Alexei Vladimirovich, don’t belittle your abilities,” said Golenishchev. “Our scouts reported the jaunty way you cut down the Gorelov librarian Marchenko, and he was no novice…”

“Comrade Latokhin,” said Akimushkin, breaking the silence, “you’re laying a great responsibility on us. If we mess things up, you’ll be left with no Book!”

“I believe in you,” Latokhin said with a helpless smile. “Comrades, I’ll tell you what I think…” He scratched the back of his head and then said in a flash of inspiration: “You have to understand that it’s not a question of physical strength, but… you could call it metaphysical strength. Our cause is just, we shall prevail in any case!”

“But what will the conditions of the duel be?” asked Zarubin.

“The Pavliks are willing to accept the initial rules,” said Latokhin, brightening up. “We have an agreed area for the field of battle; anyone can leave it if he wishes, then he’s out of bounds and the others continue, and then… it’s whoever wins, basically.”

“Humane enough, in principle,” Zarubin agreed. “OK, lads, I’m for it. A hundred deaths fewer, as they say…”

“I was in agreement right from the start,” said Golenishchev.

“Is there any alternative?” Tsofin asked with a bitter laugh.

“I’m the gregarious type,” Akimushkin told us. “Vyazintsev and Kisling, what have you decided?”

I nodded, totally overwhelmed by the situation.

Kisling shrugged: “I’m always willing…”

And Golenishchev summed up: “Comrade Latokhin, call Chakhov… We accept his terms.”